Income tax is the single most important source of revenue for the UK Treasury, accounting for about a quarter of total tax revenue.

Taxlab Taxes ExplainedIt is levied on most forms of personal income, but each individual has a personal allowance of income that can be received tax-free, and only around three-fifths of adults have income high enough to pay income tax. Above the personal allowance, income is split into bands that are taxed at different rates. The chart below shows the rate of tax paid on an additional £1 of income at different income levels. Some powers to adjust income tax are devolved to Scotland and Wales, and income tax rates in Scotland now differ slightly from those in the rest of the UK.

Savings, dividends and pensions are taxed less heavily than ordinary income. And income from employment and self-employment is subject to National Insurance contributions as well as income tax.

Note: Schedules include the impact of the withdrawal of the tax-free personal allowance at a rate of 50p for each £1 by which taxable income exceeds £100,000. ‘Child’ lines show the impact of the high-income child benefit charge (HICBC) for a parent in receipt of child benefit for one, two or three children. The HICBC imposes a tax charge equal to 1% of the total child benefit received for every £100 that taxable income exceeds £50,000. Figures assume that the taxed individual does not have a partner whose income exceeds their own.

Source: IFS Fiscal Facts, available here.

Most income is subject to income tax, including income from employment, self-employment, private and state pensions, investments and property rental. Income from certain savings products, and many state benefits, is not subject to income tax.

Money contributed to a private pension or donated to charity can be deducted from an individual’s income for income tax purposes. For example, if an individual earns £30,000 but puts £5,000 of it into a pension, then they will only be taxed on £25,000 of income (though the income later received from the pension will be taxed at that stage). The tax treatment of private pensions is discussed in more detail below.

More about what incomes do and don’t attract taxThe following are all subject to income tax:

The following are not subject to income tax:

Some items can be deducted from taxable income. Landlords and the self-employed can deduct their business expenses (or give up that right in exchange for an additional £1,000 tax-free allowance), although landlords can now only deduct their mortgage interest costs at the basic rate of tax. Employees can also deduct their work-related expenses, though the rules on what they can deduct are stricter than for the self-employed.

The table below shows income tax rates and thresholds in England, Wales and Northern Ireland (they are different in Scotland – see below).

Each individual has a personal allowance, which is the amount of income that they can receive tax-free. Only those with incomes in excess of the personal allowance pay income tax.

Above the personal allowance, different bands of income are taxed at different rates.

For historical tax rates, bands and allowances, see IFS Fiscal Facts.

Note and sourceNote: Income ranges assume the individual receives the standard personal allowance. For people with non-standard allowances – receiving the blind person’s allowance, for example, or having their personal allowance reduced by HMRC to make up for underpaying tax in the previous year – the width of the basic-rate band is unchanged, so the lower bound of the higher-rate income range will be different from that shown in the table. Numbers of taxpayers include Scottish taxpayers, who are classified as higher-rate taxpayers if they have total income above the UK higher-rate threshold or if they have non-savings, non-dividend income above the Scottish higher-rate threshold, and as basic-rate taxpayers otherwise. The number of adults classified as having income below the personal allowance is calculated as the difference between the total number of taxpayers and the total adult (i.e. aged 16+) population; the classification is not strictly accurate as the adult population and the taxpayer population can differ for reasons other than having income below the level of the personal allowance.

The table above also shows the number and share of adults in each band (including Scottish taxpayers). Only around three-fifths of the adult population have incomes high enough to pay income tax. Despite being far fewer in number, higher-rate taxpayers provide more income tax revenue than basic-rate taxpayers, and additional-rate taxpayers more than higher-rate taxpayers – a reflection of the concentration of income in the hands of the better-off as well as the higher tax rates they face.

Technical note: the difference between allowances, bands, thresholds and limitsThere is a subtle but important technical distinction between a tax allowance and a zero-rate band.

A zero-rate band is a band of income in which the tax rate happens to be 0%.

An allowance, in contrast, is an amount that can be deducted from taxable income.

In both cases, the amount in question does not get taxed.

But if a zero-rate band is made bigger, by default it ‘eats into’ the band above it, so that other thresholds are unchanged. The untaxed income would otherwise have been taxed at the rate applying to the band above.

In contrast, since an allowance is deducted from taxable income, increasing it leaves the width of all tax bands unchanged. It is equivalent to having a zero-rate band covering the first part of someone’s income but also moving other thresholds up in unison by the same amount. The untaxed income would otherwise have been taxed at the individual’s top marginal rate The amount of additional tax due as a percentage of each additional £1 of a tax base (such as income). Read more .

An increase in the personal allowance, leaving the width of the basic-rate band unchanged, thus automatically increases the income level at which higher-rate tax becomes payable (the higher-rate threshold).

This matters for several practical applications:

The personal allowance is gradually withdrawn from individuals with incomes over £100,000 a year, creating an effective 60% tax rate on incomes between £100,000 and £125,140. In a similar fashion, families receiving child benefit have it withdrawn when the highest-income parent’s income exceeds £50,000.

If a person’s income is below the personal allowance, they can choose to transfer 10% of the full allowance (rounded to the nearest £10) to a spouse or civil partner who is a basic-rate taxpayer.

More about withdrawal of the personal allowance and child benefitFor every £1 by which an individual’s income exceeds £100,000, their personal allowance is reduced by 50p. The result is that, for an individual with income of £100,000, each additional £1 of income incurs 60p of income tax. The £1 of additional income is subject to 40% higher-rate tax (meaning tax of 40p); on top of that, an extra 50p becomes taxable at 40% as a result of the withdrawal of 50p of tax-free allowance, such that an extra 20p of tax is due, making 60p in total.

The consequence of this policy is to create a ‘hump’ in the marginal income tax schedule: an effective 60% income tax band, twice the width of the personal allowance, above £100,000 (see the chart at the start of this article).

In addition, families receiving child benefit in effect have it reduced by 1% for every £100 by which the highest-income parent’s income exceeds £50,000. This creates additional effective tax rates between £50,000 and £60,000 which depend on the amount of child benefit received and so the number of dependent children in the family. Families with someone on more than £60,000 have their child benefit withdrawn completely; some therefore opt out of receiving it, rather than claiming it and then having it clawed back through income tax. In effect, income tax is used as a mechanism to means-test child benefit.

More about income tax and marriageThe marriage allowance reduces the tax bill of married couples and civil partners where one is a basic-rate taxpayer and the other is a non-taxpayer. A person whose income is below the personal allowance can choose to transfer 10% of their personal allowance (rounded to the nearest £10) to a spouse or civil partner who is a basic-rate taxpayer. As a basic-rate taxpayer, the recipient sees their tax liability reduced by 20% of the amount transferred – currently saving them up to £252 in tax, since the personal allowance is £12,570.

One anomaly that arises from the marriage allowance is that eligible individuals who cross over from being basic-rate taxpayers to higher-rate taxpayers can see their tax bill jump up. For individuals able to claim the maximum marriage allowance, an increase in their income from just below to just above the higher-rate threshold results in a £251.40 increase in their tax bill because of the loss of the marriage allowance.

The dwindling number of married couples and civil partners in which one partner was born before 6 April 1935 can choose to claim the (more generous) married couple’s allowance (MCA) instead of the marriage allowance.

Most income tax bands and allowances increase automatically at the start of each tax year (in April) in line with inflation Inflation is the change in prices for goods and services over time. Read more (as measured by the Consumer Prices Index, CPI), unless parliament intervenes. This mitigates a phenomenon known as fiscal drag, whereby income growth pulls ever more taxpayers into higher tax bands. However, a number of new thresholds introduced since 2010 do not increase with inflation Inflation is the change in prices for goods and services over time. Read more in this way: these include the £100,000 threshold at which the personal allowance starts to be withdrawn and the £50,000 threshold at which child benefit starts to be withdrawn. As a result, the number of people affected by these high effective rates of tax has grown rapidly since their introduction.

One big change to income tax in recent years was the large increase, over the 2010s, in the level of the personal allowance. In the second half of the 2010s, there was also a large rise in the higher-rate threshold, albeit following an even larger real-terms reduction earlier in the decade. However, the government changed direction in 2021. All income tax thresholds, including the personal allowance and the higher-rate threshold, will be frozen in cash terms at their 2021–22 levels up to and including 2027–28. This is forecast to result in a substantial reduction in the real-terms value of both.

Details of changes in the personal allowance and higher-rate threshold over timeThe charts below show the large changes to the levels of the personal allowance and the higher-rate threshold that have been enacted in recent years. Between 1990–91 and 2007–08, the personal allowance and the higher-rate threshold both grew in real terms (that is, adjusting for inflation Inflation is the change in prices for goods and services over time. Read more ) by 1% a year on average – slower than growth in average earnings. After 2007–08, however, there was a sustained move to increase the personal allowance, which increased in real terms by more than 5% a year on average between 2007–08 and 2019–20 (a cumulative 82% over that 12-year period) – taking it from 24% to 44% of average earnings, which grew only slowly over that period. In the first half of the 2010s, the higher-rate threshold was reduced sharply, more than offsetting higher-rate taxpayers’ gains from the increased personal allowance; however, the Conservative government changed course in the second half of the decade, increasing the higher-rate threshold to £50,000.

In its 2021 Spring Budget, the government changed direction again – perhaps mindful of the need to raise revenue after the COVID-19 crisis – announcing that all income tax thresholds will be frozen in cash terms at their 2021–22 levels up to and including 2025–26; subsequently extended to 2027–28. This will amount to a real-terms reduction of thresholds over the period, although current forecasts suggest this will reverse only a fraction of the rise in the personal allowance seen in the previous decade.

Allowances from IFS Fiscal Facts income tax table. Historical allowances adjusted for inflation using the Consumer Prices Index (ONS series D7BT). Average earnings figure is 52 x average weekly earnings (AWE; ONS series KA46 and MD9M). Forecasts for CPI and average earnings from Office for Budget Responsibility, https://obr.uk/efo/economic-and-fiscal-outlook-march-2023/.

Thresholds from IFS Fiscal Facts income tax table. Historical thresholds adjusted for inflation using the Consumer Prices Index (ONS series D7BT). Average earnings figure is 52 x average weekly earnings (AWE, ONS series KA46 and MD9M). Forecasts for CPI and average earnings from Office for Budget Responsibility, https://obr.uk/efo/economic-and-fiscal-outlook-march-2023/.

Income from savings and investments is taxed differently from other income. Income from savings and investments held in an Individual Savings Account (ISA) is completely exempt from tax. Each individual is also allowed to receive certain amounts of interest income and dividends outside ISAs free of tax. And dividends that are still subject to tax are taxed at reduced rates. When calculating which income falls into which tax band, dividends are treated as the top slice of income, followed by interest income.

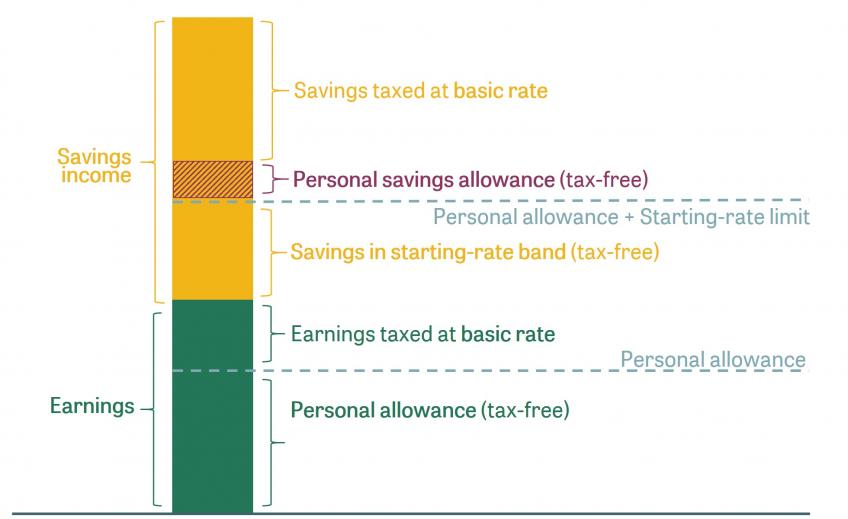

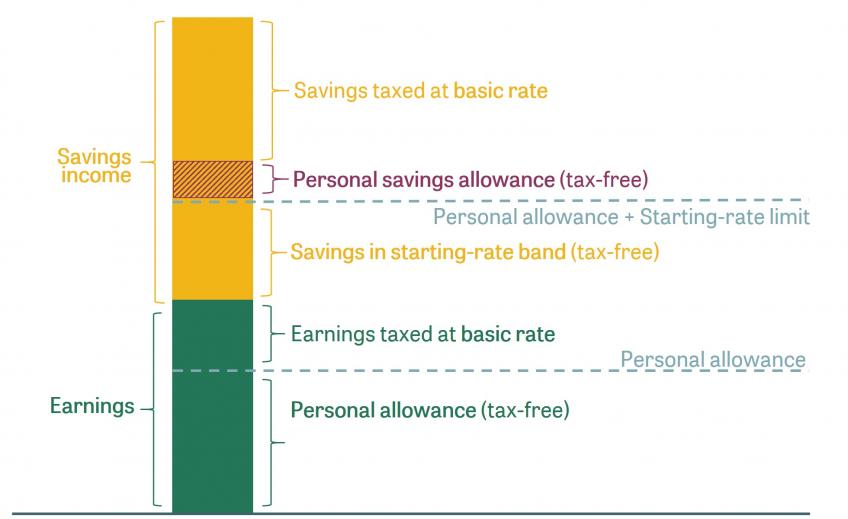

More about taxation of interest incomeSavings income – interest earned on deposits with banks or building societies – is subject to standard income tax rates, except that there are two specific provisions which in practice take much of it out of tax:

The chart below (not to scale) shows another example where both the personal allowance and the starting rate for savings would be relevant. In 2023–24, someone with £15,000 of earnings and £10,000 of savings income will pay income tax on £2,430 of earnings and £6,430 of savings income. The personal allowance covers the first £12,570 of earnings, with the remaining £2,430 of earnings taxed at the basic rate. Up to the starting-rate limit of £17,570 of total income (£5,000 above the personal allowance), savings income is tax-free; with earnings of £15,000, that means the first £2,570 of savings income falls within the starting-rate band and is untaxed. Above that, the next £1,000 of savings income is covered by the personal savings allowance and is also untaxed, leaving £6,430 of savings income (£10,000 minus £2,570 minus £1,000) to be taxed at the basic rate.

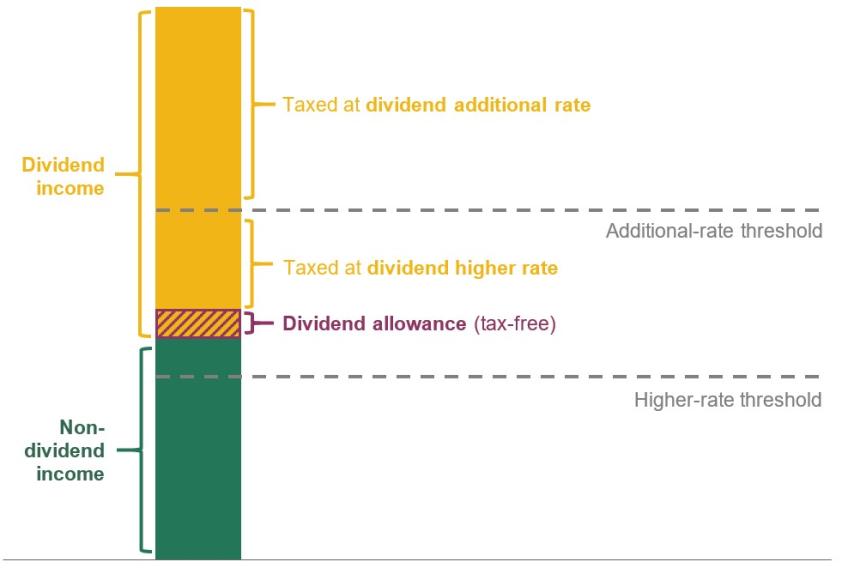

A specific dividend allowance is available to those who receive income from dividends on shares. This exempts the first £1,000 a year of dividend income from tax (and, like the personal savings allowance, it is strictly a nil-rate band rather than an allowance). Unlike the personal savings allowance, this dividend allowance does not vary with an individual’s tax rate.

Dividend income in excess of the dividend allowance is taxed at lower rates than other forms of income (see the table). The chart below provides an example in which dividend income would be taxed at both the higher and additional dividend rates. Note that, as mentioned above, dividends are treated as the top slice of income when deciding which income falls into which band.

Individuals can place up to £20,000 a year in an ISA. These savings can either be held in cash or invested in financial assets such as shares and bonds. Any income made on savings held in an ISA – any interest or dividends – is entirely exempt from income tax (and any capital gains are exempt from capital gains tax).

People aged under 50 can put up to £4,000 of their £20,000 ISA allowance into a Lifetime ISA (LISA), as long as they made their first contribution when aged 18–39. The government will add a 25% top-up to anything paid into a LISA, as well as any investment income being tax-free. Savings in a LISA can be freely withdrawn from the age of 60, or earlier if used alongside a mortgage to buy the saver’s first home for £450,000 or less. However, money withdrawn from a LISA before age 60 for any other reason is subject to a 25% charge – more than the value of the original government top-up.

Pension income is treated as (deferred) earnings for tax purposes. Broadly speaking, income that is paid into a pension is exempt from tax, income earned within the pension fund is also exempt, but money received from the pension is taxed instead (although 25% can be taken free of tax). There is an annual cap on the amount that can be saved in a pension. This cap has been reduced significantly in recent years – although it saw a (relatively modest) increase in April 2023. Prior to April 2023, there was also a lifetime cap, but this has now been abolished.

Note: Years refer to financial years, so, for example, ‘2020’ refers to 2020–21.

More about the taxation of private pensionsIf an individual puts money into a pension scheme – or their employer does on their behalf – the money paid in is excluded from the individual’s taxable income. This applies to pension contributions up to the annual allowance shown in the chart above (or 100% of annual earnings, if lower), but the annual allowance is reduced for the highest-income individuals: specifically, if someone’s income excluding pension contributions exceeds £200,000, the annual allowance is reduced by £1 for every £2 by which the individual’s income including pension contributions exceeds £260,000, until it reaches a minimum level of £10,000 for those whose income including pension contributions exceeds £360,000.

In addition to this annual cap on contributions, there was previously a lifetime allowance (see chart above) which the total value of an individual’s pension pot could not exceed without incurring penal tax rates. The lifetime allowance was abolished entirely at the 2023 Spring Budget.

The 2010s saw large reductions in the annual and, to a lesser extent, lifetime allowances (see chart above), as well as the introduction of ‘tapering’ away of annual allowances for high earners described above. These steep reductions greatly reduced the tax relief available to those with the resources to make large contributions to their pensions. This was at least partially reversed by the abolition of the lifetime allowance.

Income (and capital gains) received from investments within a pension scheme are free of personal tax while the money remains within the pension scheme. But money withdrawn from a pension – as a regular income or as an ad hoc withdrawal – is taxed like any other form of income. In effect, income tax on earnings paid into a pension is deferred until the earnings (and any investment returns earned in the meantime) are received from the pension and available to spend. The exception to this is that people are entitled to withdraw 25% of their pension pot free of income tax. This 25% escapes income tax entirely, as income tax is paid neither at the point of contribution nor at the point of withdrawal.

The way pensions are treated for income tax is very different from the way they are treated for National Insurance contributions: employer pension contributions are excluded from income for NICs purposes (as for income tax) but employee contributions are not, and no NICs are levied on pension income at all.

The Scottish and Welsh parliaments both have the power to make certain changes to the rates of income tax within their jurisdictions. These powers do not apply to savings and dividend income, which continue to be taxed on a consistent basis across the UK.

So far, only the Scottish Parliament has chosen to use these powers, creating a separate system of rates and bands for Scottish taxpayers.

More about income tax in ScotlandThe Scotland Act 2012 and Scotland Act 2016 greatly expanded the powers devolved to the Scottish Parliament to set its own income tax rates and bands (though not the tax-free personal allowance) for residents of Scotland, except for income from savings and dividends, which continue to be taxed at UK-wide rates. Scotland has used these powers to set slightly different rates and bands from the rest of the UK. The table below shows the current income tax bands and rates in Scotland, along with the number of people in each band; the chart at the very start of this article shows how the rate schedule compares with that in the rest of the UK.

Note and sourceNote: Income ranges assume the individual receives the standard personal allowance. Taxpayers classified according to the highest band in which they have non-savings, non-dividend income: some will have savings or dividend income in a higher band. The number of adults classified as having income below the personal allowance is calculated as the difference between the total number of taxpayers and the total adult (i.e. aged 16+) population of Scotland; the classification is not strictly accurate as the adult population and the taxpayer population can differ for reasons other than having income below the level of the personal allowance.

*Most recent year for which data were available.

The most eye-catching changes in Scotland have been to tax rates: the introduction of two new bands, taxed at 19% and 21%, either side of the 20% basic-rate band, and increases in the higher and additional rates of tax. Increasing the higher rate to 42% also means that the effective tax rate between £100,000 and £125,140, caused by the withdrawal of the personal allowance, is 63%, compared with 60% in the rest of the UK. The biggest difference from the rest of the UK, however, is in the higher-rate threshold. It has risen by only a small amount in cash terms since being devolved (it was £43,000 in 2016–17), whereas the threshold in the rest of the UK has been increased more rapidly. This means that, in real terms, the higher-rate threshold has fallen by more in Scotland than in the rest of the UK.

The chart below shows the difference between income tax liabilities in Scotland and the rest of the UK at a given income level. The 19% starter rate means that just under half of Scottish income tax payers pay less income tax in Scotland than they would in the rest of the UK. But the difference is small: the maximum gain in 2023–24, for example, is £21.62, which applies to those in the Scottish basic-rate band. Those in the starter-rate band or near the bottom of the intermediate-rate band gain less than this, as do those in receipt of means-tested benefits, who see their higher after-tax income partly offset by reduced benefit entitlements.

In contrast, those with higher incomes pay significantly more tax in Scotland than they would in the rest of the UK (see chart below) – a result of the lower higher-rate threshold in Scotland as well as the higher rates.

Assumes income is not from savings or dividends.

More about income tax in WalesSince 2019–20, the Welsh Parliament has had the power to set the rates – though not the bands – of income tax for residents of Wales. These rates cannot be more than 10 percentage points lower than the rates that apply in England and Northern Ireland. The Welsh Parliament has so far chosen to leave the Welsh rates of income tax unchanged. Welsh taxpayers therefore face the same tax schedule as those in England and Northern Ireland.

Most income tax is deducted from income ‘at source’ by employers and pension providers through the Pay-As-You-Earn (PAYE) system and passed on to the government by them. Only a minority of taxpayers must fill in a tax return at the end of the year.

More about PAYE and self-assessmentThe PAYE system involves employers (and pension providers) deducting income tax from earnings (and pensions) on an exact cumulative basis – i.e. when calculating tax due each week or month, the employer considers income not simply for the period in question but for the whole of the tax year to date. Tax due on total cumulative income is calculated and tax paid thus far is deducted, giving a figure for tax due this week or month. The cumulative system means that, at the end of the tax year, the correct amount of tax should have been deducted – at least for those with relatively simple affairs – whereas under a non-cumulative system (in which only income in the current week or month is considered), an end-of-year adjustment might be necessary.

Taxpayers with more complicated affairs – such as the self-employed, those with very high incomes, company directors and landlords – must fill in a self-assessment tax return after the end of the tax year, setting down their incomes from different sources and any tax-privileged outgoings such as pension contributions or gifts to charity; HMRC Her Majesty’s Revenue and Customs (HMRC) is the UK government body responsible for the collection and administration of most taxes. Read more will calculate the tax owed given this information. Tax returns must be filed by 31 October if completed on paper or by 31 January if completed online. If people paid the tax due only when they submitted their tax return, they would be paying significantly in arrears, since the tax return can be filed almost 10 months after the end of the tax year in question (if done online). Most taxpayers subject to self-assessment must therefore make two ‘payments on account’ ahead of that – by 31 January of the tax year in question and by 31 July following the end of the tax year – each equal to half their tax bill from the previous year. For the 2021–22 tax year, for example, they had to make payments on account equal to half their 2020–21 liability in each of January 2022 and July 2022. When submitting their 2021–22 tax return by the end of January 2023 they then had to pay (or be refunded) the difference between what they had paid so far and their final liability for 2021–22. This is in addition to making their first payment on account for 2022–23 (equal to half their final 2021–22 liability). Fixed penalties and surcharges operate for those failing to make their returns by the deadlines and for underpayment of tax.

PAYE works well for most people most of the time, sparing just over three-fifths of taxpayers from the need to fill in a tax return. The UK is unusual internationally in not requiring most people to fill in a tax return. However, in a significant minority of cases, the wrong amount is withheld – typically when people have more than one source of PAYE income during the year (for example, more than one job/pension over the course of the year), especially if their circumstances change frequently or towards the end of the year. Such cases can be troublesome to reconcile later on. Since April 2013, employers have been obliged to report salary payments to HMRC Her Majesty’s Revenue and Customs (HMRC) is the UK government body responsible for the collection and administration of most taxes. Read more in real time, rather than just at the end of the year. This should allow HMRC Her Majesty’s Revenue and Customs (HMRC) is the UK government body responsible for the collection and administration of most taxes. Read more to calculate tax liabilities and make any necessary adjustments more quickly based on real-time knowledge of individuals’ income from all sources. In December 2015, the government also launched ‘personal tax accounts’, enabling people to see and manage more of their tax information online.

More change is on the way. As part of the government’s ‘Making Tax Digital’ agenda, from April 2026 self-employed people and landlords with turnover of more than £50,000 a year will be required to keep records digitally and send an electronic summary of income and expenses to HMRC Her Majesty’s Revenue and Customs (HMRC) is the UK government body responsible for the collection and administration of most taxes. Read more every three months during the year, with a finalisation and declaration by 31 January following the end of the year instead of a self-assessment tax return. (Those who are ‘digitally excluded’ and cannot do this will be exempt.) The new system is currently being piloted with volunteer businesses and landlords to test it before it becomes mandatory.

The modernisation and digitisation of tax administration are welcome. But such changes can cause major headaches if they go wrong. Implementing the new system smoothly is a major challenge for the government.

This section shows changes in the number of people paying any income tax and paying higher rates, sets out that income tax is progressive A tax is progressive if tax liability increases more than in proportion to the tax base, or to income. Read more and shows how much revenue comes from different parts of the income distribution.

Only about three-fifths of adults have income high enough to pay income tax. More people than this are affected by income tax, because a higher proportion live in a family in which someone pays income tax, and a higher proportion still will pay income tax at some point in their lives. But even so, income tax reductions are poorly targeted as a way to help the poorest in society.

The charts below show that the proportion of the population paying any income tax rose steadily through most of the 1990s and 2000s but fell from the late 2000s onwards as a result of the big increases in the personal allowance (described above). The trend has reversed again in the early 2020s thanks to a cash freeze in the personal allowance, undoing the reductions seen after 2007–08. The share of adults paying higher rates of income tax, meanwhile, has risen sharply since the early 1990s and is currently increasing particularly rapidly as a result of the cash freeze to the higher-rate threshold.